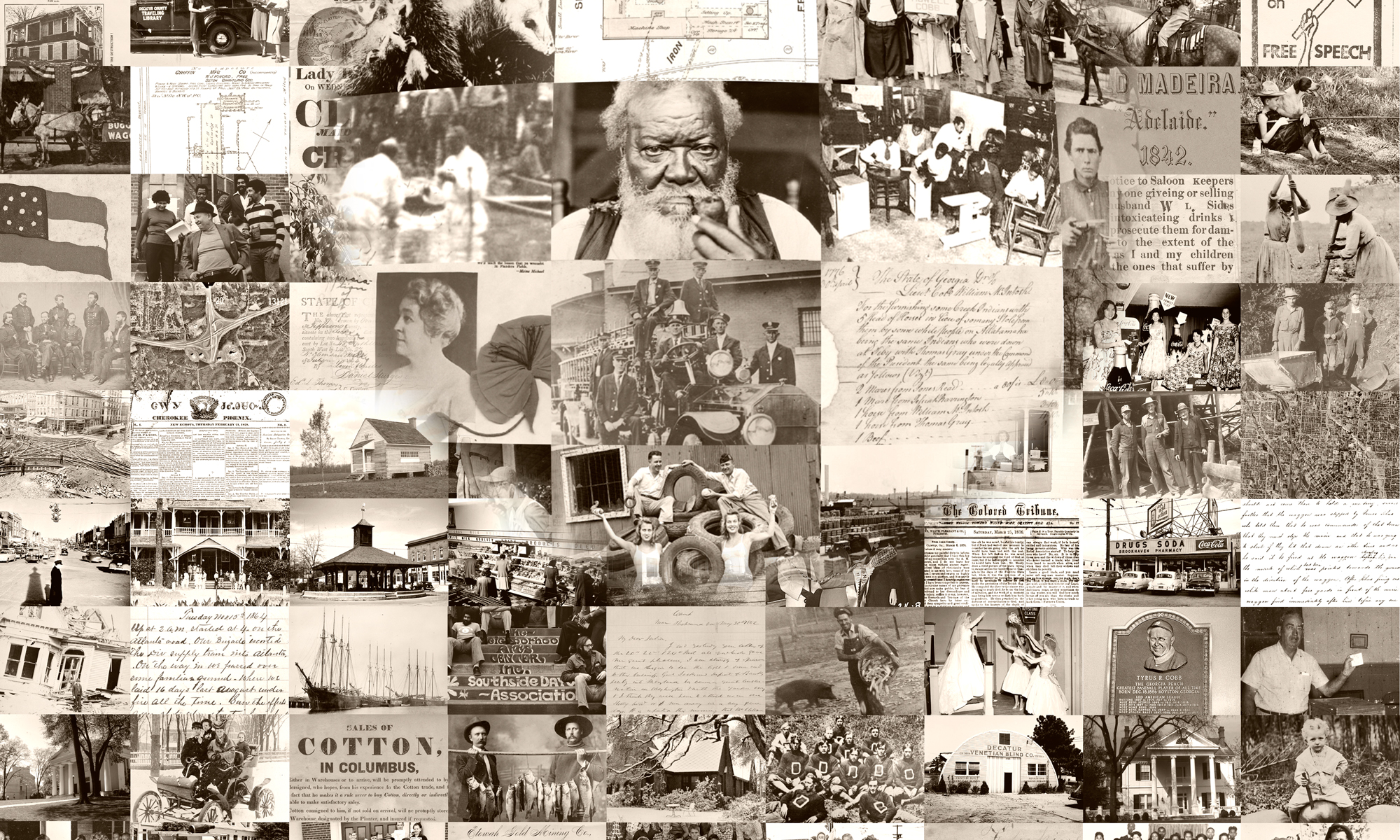

This press release is part of a series of guest posts contributed by our partners at HomePLACE, a project of the Georgia Public Library Service. HomePLACE works with Georgia’s public libraries and related institutions to digitize historical content for inclusion in the Digital Library of Georgia.

ATLANTA, Ga — Georgia HomePLACE and the Digital Library of Georgia (DLG) are pleased to announce the addition of over 16,000 pages of the Walker County Messenger dating from 1880-1924 to the Georgia Historic Newspapers (GHN) website. Consisting of over 2,100 searchable issues, the Walker County Messenger archive provides historical images that are both full-text searchable and can be browsed by date. Issues are freely available online through the GHN: https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu.

LaFayette’s first newspaper, the Walker County Messenger, was established by Captain Augustus McHan and his son E. A. McHan on July 27, 1877. In its first year, the Messenger was a six-column, four-page paper that sold for a yearly subscription of one dollar. The paper would serve as the legal organ for not only Walker County but also Chattooga, Catoosa and Dade counties until those regions founded their own newspapers in later years. Today, the Walker County Messenger continues to serve the citizens of LaFayette under the ownership of the Times-Journal Inc.

“Newspapers and libraries keep the pulse of a community, and both are critical to quality research. Access to information resources is one of the core values of Georgia’s public libraries, and we are so pleased to help support our partners at the Digital Library of Georgia in making these newspapers freely available online,” said State Librarian Julie Walker.

Historic newspaper pages are consistently the most visited of any DLG sites. The GHN is compatible with all current browsers, and the newspaper page images can be viewed without the use of plug-ins or additional software downloads. Annually, DLG digitizes over 100,000 historic newspaper pages with funding from GALILEO, Georgia Public Library Service, and its partners and microfilms more than 200 current newspapers.

“The significance of our local newspaper being available for full-text searching and browsing by anyone with access to the internet cannot be overstated. We feel very fortunate that our local organ was selected by DLG and Georgia HomePLACE for digitization,” said Cherokee Regional Library System Director Lecia Eubanks.

The GHN includes some of the state’s earliest newspapers providing perspectives often missing in history books, including important African-American, Roman Catholic and Cherokee newspapers, as well as local and regional papers from across the state. All previously digitized newspapers are scheduled to be incorporated into the new GHN platform. Until that time, users may continue to access the existing online regional and city sites.

Georgia HomePLACE http://georgialibraries.org/homeplace/ is a project of the Georgia Public Library Service (GPLS) that encourages public libraries and related institutions across the state to participate in the Digital Library of Georgia. HomePLACE offers a highly collaborative model for digitizing primary source collections related to local history and genealogy. HomePLACE is supported with federal Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA) funds administered by the Institute of Museum and Library Services through GPLS, a unit of the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia.

Based at the University of Georgia Libraries, the Digital Library of Georgia http://dlg.galileo.usg.edu/ is a GALILEO initiative that collaborates with Georgia’s libraries, archives, museums and other institutions of education and culture to provide access to key information resources on Georgia history, culture and life. This primary mission is accomplished through the ongoing development, maintenance and preservation of digital collections and online digital library resources. DLG also serves as Georgia’s service hub for the Digital Public Library of America and as the home of the Georgia Newspaper Project, the state’s historic newspaper microfilming project.

CONTACT: Angela Stanley, astanley@georgialibraries.org, (404) 235-7134