In 2011, we received a donation of films from Pebble Hill Plantation in Thomasville, Georgia, spanning from 1916 into the 1970s. Pebble Hill was the winter hunting retreat for the Hanna family of Cleveland, Ohio, prominent industrialists and politicians.

One of the most important segments of all the films in the collection was 26 seconds of 28mm film showing Pebble Hill’s black baseball team playing Chinquapin Plantation’s black baseball team sometime in the 1910s or 1920s. We knew right away that this was unique footage and would be of interest to many people, so once the collection was more fully processed and the film preserved to a new substrate and digitized, we began to publicize it. An article in the New York Times on April 30, 2013, gave us worldwide publicity.

The head of the Negro Leagues Museum then speculated that this might be the earliest footage of African Americans playing baseball. I presented the footage and spoke at the 2014 Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture at the National Baseball Hall of Fame. My co-presenter on the panel was professor Leslie Heaphy of Kent State University, the editor of the journal Black Ball: New Research in African American Baseball History. She encouraged me to write up the story of the film and my research into dating it more precisely (to find out if it really was the earliest surviving black baseball footage) for her journal, which I was finally able to do in 2018, and volume 10 of that journal is now out with my article.

Describing my research into the film involved more than just telling my general knowledge about film after 20 years of working in a film archives. I had to document how and where I learned about the history of 28mm film, Pathéscope cameras and projectors, home movies, Pebble Hill, the baseball team, and South Georgia baseball in general. I combed Pebble Hill’s private archives, browsed books on the local history of the county, contacted colleagues at the Jack Hadley Black History Museum and the Thomasville History Center, looked into the accounts of other South Georgia plantations, explored Hanna family history in Ohio, and peppered the staff of Pebble Hill with many questions.

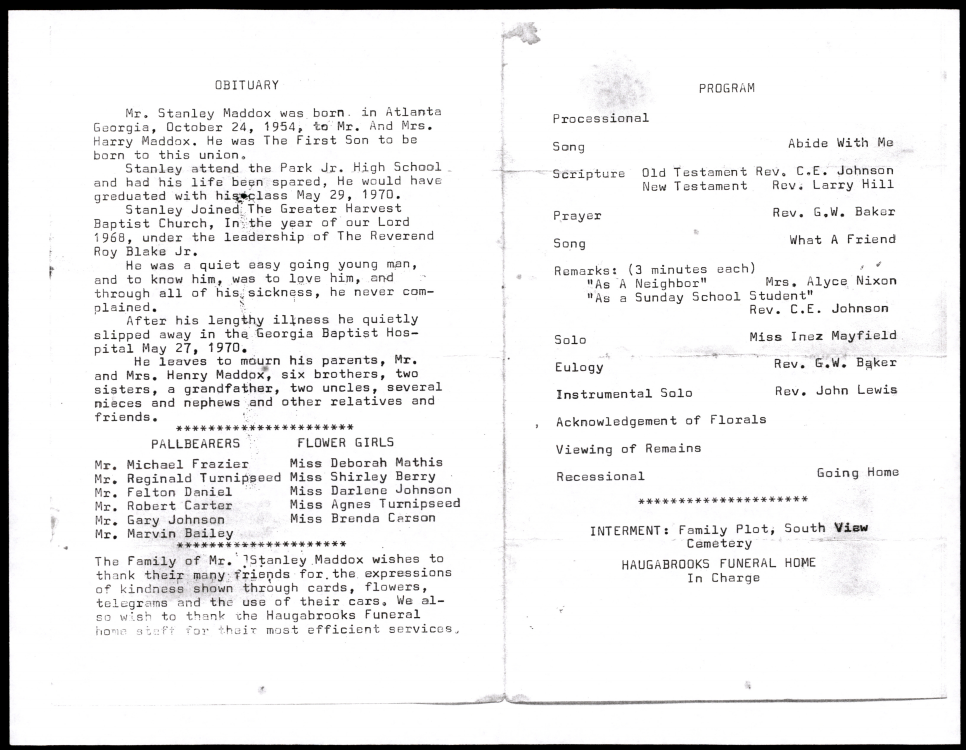

Very helpfully, the Pebble Hill archives also contain Pansy Hanna Ireland Poe’s diary covering the years in question, 1915-1925, though the handwriting is challenging to read. I even needed weather reports from newspapers and climatological websites that could tell me what the weather was like at certain times of the year. Finally, I required obituaries, mentions of the hospital, and social event data.

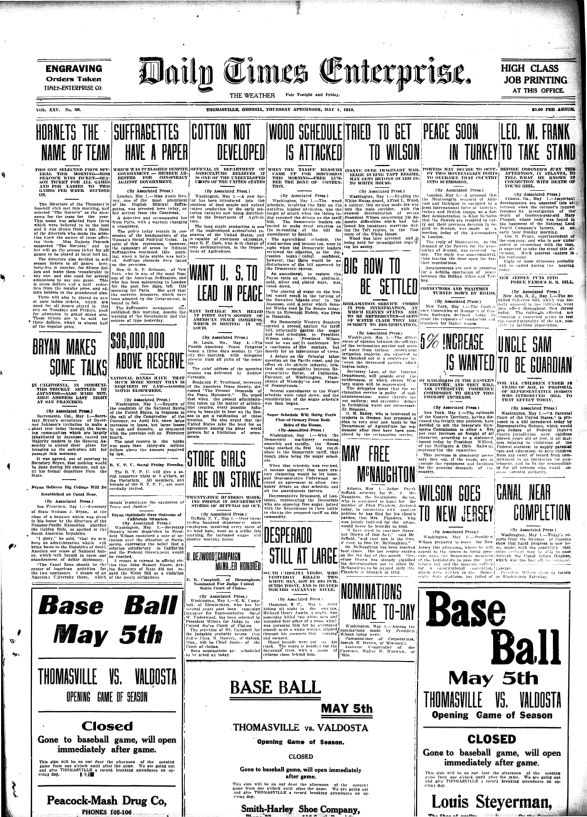

Thankfully, the Digital Library of Georgia had already digitized many newspapers from the region (full-text searchable!). This work saved me many hours of peering at and being made dizzy and cross-eyed from reading small-print newspapers of the nineteen-teens on microfilm readers.

The newspapers gave me a sense of what was important in the area between 1915 and 1925, visitors to the town, what the weather was like, what townsfolk were doing. To provide context to the story of this film, I was looking for any mention of regional hunting plantations, baseball teams, or games, a general sense of baseball in the area, what other teams existed, and mentions of African American ballplayers.

One of my favorite issues of the digitized Thomasville Daily Times-Enterprise is from May 1, 1913, several days ahead of the town’s opening day of the baseball season. Almost every page in that issue contains notices from businesses in town letting everyone know that on May 5, opening day, they’d be “Closed. Gone to baseball game. Will open immediately after game.”

As William Warren Rogers stated in his books on Thomas County, baseball was an obsession in Thomasville. I could see that it really was a baseball-mad town. This helps explain why local plantations had baseball teams, though I have also been disappointed to see that black plantation team results of those years are rarely mentioned. Some non-plantation black team games are mentioned, though not nearly as much detail as white town teams.

I will always be looking for more information from South Georgia that will illuminate stories from Pebble Hill, and the DLG is one of my best sources.

—Margaret Compton

Film Archivist

Walter J. Brown Media Archives and Peabody Awards Collection