Counties in Georgia had the right to vote for prohibition since 1885. Most had done so by 1907, the year that state wide prohibition was passed. Georgia’s fervor for temperance ran well in advance of the national mood with the state enacting prohibition sooner and holding on to it longer than most of the country. Nationally, the Volstead Act of 1919 enforced prohibition as established by ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment. Repeal would come with passage of the Twenty-first Amendment in 1933; Georgia delayed repeal until 1935 and retains some dry and partially dry counties to this day.

Counties in Georgia had the right to vote for prohibition since 1885. Most had done so by 1907, the year that state wide prohibition was passed. Georgia’s fervor for temperance ran well in advance of the national mood with the state enacting prohibition sooner and holding on to it longer than most of the country. Nationally, the Volstead Act of 1919 enforced prohibition as established by ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment. Repeal would come with passage of the Twenty-first Amendment in 1933; Georgia delayed repeal until 1935 and retains some dry and partially dry counties to this day.

This era in the United States’ history is popularly understood through images of speakeasies, bootlegging, stills and police raids. This weekend on PBS, documentarian Ken Burns brings his trademark style and focus to bear on the subject in a new film titled, simply, Prohibition. Figuring you might be as excited as we are, and hoping your curiosity will be piqued, we want to share some resources available through the DLG for learning more about prohibition in Georgia.

This era in the United States’ history is popularly understood through images of speakeasies, bootlegging, stills and police raids. This weekend on PBS, documentarian Ken Burns brings his trademark style and focus to bear on the subject in a new film titled, simply, Prohibition. Figuring you might be as excited as we are, and hoping your curiosity will be piqued, we want to share some resources available through the DLG for learning more about prohibition in Georgia.

For a day to day glimpse of the forces at work in promoting temperance, the legislative sparring by elected officials and the reactions of citizens both dry and ‘wet,’ start with the Georgia Historic Newspapers. A search for the term ‘temperance,’ prohibition’ or ‘bootlegging’ in any of the newspapers returns a plethora of local news: the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union holding rallies in cities across Georgia; an African American barber raided on suspicion of bootlegging (stoking racial animosity was an integral part of the fight against alcohol); attempts to circumvent prohibition by passing a medicinal beer law (sound familiar?).

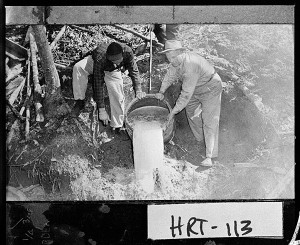

In the Vanishing Georgia collection you will find photographs of stills, moonshiners and busted moonshine operations. Moonshine has a long history in Georgia, one that continued after Prohibition. There are also photographs of citizens as they convene on their local courthouses to vote on prohibition measures.

There are also photographs of citizens as they convene on their local courthouses to vote on prohibition measures.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia has entries on the temperance movement and some of its most important figures, such as the temperance leader and suffragist Mary Latimer McLendon. A fountain in her name was placed in the state capital upon her death by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

And finally, the Georgia Historic Books collection provides access to texts from the era, such as Sam Small’s Pleas for Prohibition in which he writes of liquor sales, “No process has ever been found, by priest or publicist, whereby it can be transmuted from a curse to a blessing.” Or, if you have the time, there is Henry Anselm Scomp’s eight hundred page opus on the history of the temperance movement in Georgia, King Alcohol in the Realm of King Cotton.

provides access to texts from the era, such as Sam Small’s Pleas for Prohibition in which he writes of liquor sales, “No process has ever been found, by priest or publicist, whereby it can be transmuted from a curse to a blessing.” Or, if you have the time, there is Henry Anselm Scomp’s eight hundred page opus on the history of the temperance movement in Georgia, King Alcohol in the Realm of King Cotton.