Selected by statewide cultural heritage stakeholders and funded by the Digital Library of Georgia’s competitive digitization grant program, a compelling collection of scrapbooks and photos spanning the years 1926 to 2000 now illuminates the rich history of Athens, Georgia’s Chase Street Elementary School. This newest collaboration between the DLG and Athens-Clarke County Library is accessible at the following link:

Chase Street Parent Teacher Organization (PTO) Scrapbooks

The collection, consisting of seventeen meticulously crafted scrapbooks and a photo album, encapsulates the social tapestry of a small-town Georgia schoolhouse throughout the twentieth century. An invaluable historical resource that Chase Street Elementary school parents created, these materials showcase the school’s evolution and provide unique insights into the broader Southern community school movement, popular cultural expression, and the impact of world events on a small town.

Ashley Shull, Archives & Special Collections Coordinator at the Athens Regional Library System and Jessica Varsa, Community Archivist and Chase Street PTO board member, emphasize the significance of these scrapbooks:

“The Chase Street School scrapbooks are an intact historical depiction of a neighborhood school in a rapidly changing Athens-Clarke County, Georgia community. They are a valuable resource for researchers and community members chronicling race, education governance, cultural traditions, and community relations in the south.”

Of particular note is the appearance of Johnnie Lay Burks, the pioneering first African-American teacher at Chase Street Elementary. She commenced her tenure in 1966 and appeared in the 1965-1966 scrapbook in a group faculty photo. African American students can be seen through candid class photos at the same time when Chase Street School became accessible to its first African American students during that school year. These records support research on school desegregation, offering a distinct perspective absent from traditional sources such as newspaper articles and school board minutes. On November 3, 2023, Chase Street Elementary School was renamed Johnnie Lay Burks Elementary School, honoring the legacy of its trailblazing educator.

The scrapbooks not only capture dramatic student plays, exhibits, holidays, handiwork, and special programs but also shed light on the school’s social culture, detailing PTO meetings, the responsibilities of early officers, and the structure of these unique gatherings. Due to their nomadic existence over the past 70 years, the degradation of these records has underscored the urgency of digitization to ensure their access and preservation for future generations.

The digitized images are freely available to the public. They are a valuable resource for researchers outside of Athens exploring organizational architecture, early 20th-century education in Georgia and the Southeast, and the often-overlooked contributions of parent-teacher organizations.

The scrapbooks serve as a testament to the enduring legacy of Chase Street School, reflecting the community’s resilience and commitment to education.

About the Athens-Clarke County Library

The Athens Clarke County Library creates a welcoming and inclusive environment that empowers individuals and communities by providing resources that encourage discovery, imagination, and life-long learning. The Heritage Room, the headquarters of the Archives and Special Collections Department, is located on the 2nd floor of the Athens-Clarke County Library, 2025 Baxter St., Athens, Georgia, 30605. It houses a non-circulating collection of local history, genealogy, and southern history books, microfilm, and archival materials. Visit the Athens-Clarke County Library at: https://athenslibrary.org/location/athens-clarke

About the Digital Library of Georgia

The Digital Library of Georgia (DLG) is Georgia’s statewide cultural heritage digitization initiative. It is a joint project between the University of Georgia Libraries and GALILEO. The DLG collaborates with Georgia’s cultural heritage and educational institutions to provide free online access to historic resources in Georgia. The DLG develops, maintains, and preserves digital collections and online resources and partners to build digitization capacity and technical infrastructure. It acts as Georgia’s service hub for the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) and facilitates cooperative digitization initiatives. The DLG serves as the home of the Georgia Newspaper Project, Georgia’s print journalism preservation project.

Selected images from the collection:

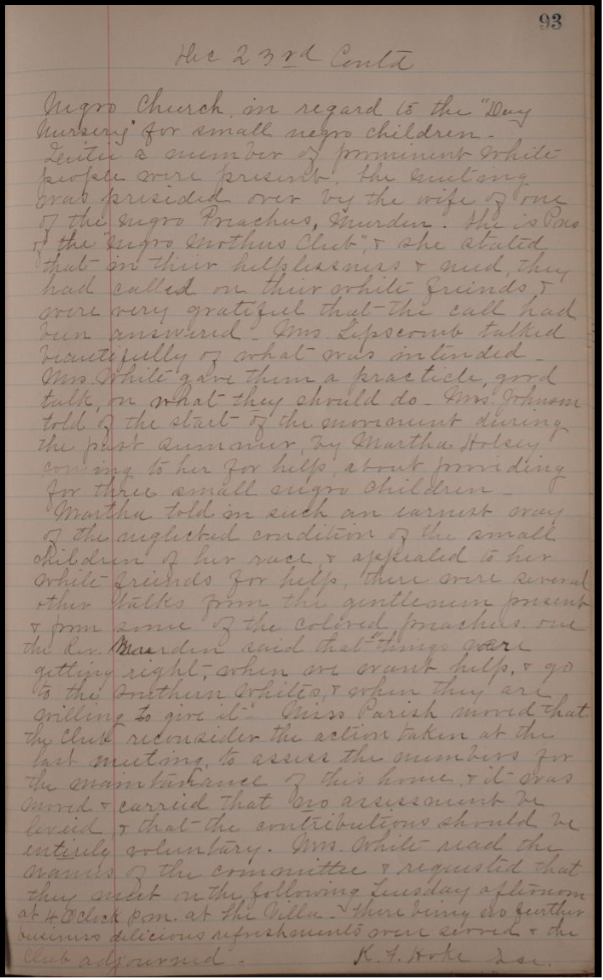

Title: Chase Street Elementary School Parent Teacher Association 1926-1929 scrapbook, page 38

URL: https://dlg.usg.edu/record/arl_ptos_sb-1926-29

Collection: Chase Street Parent Teacher Organization (PTO) scrapbooks

Courtesy of the Athens-Clarke County Library

Description: Caption: “November 1939” (images from the 1930s appear in this book

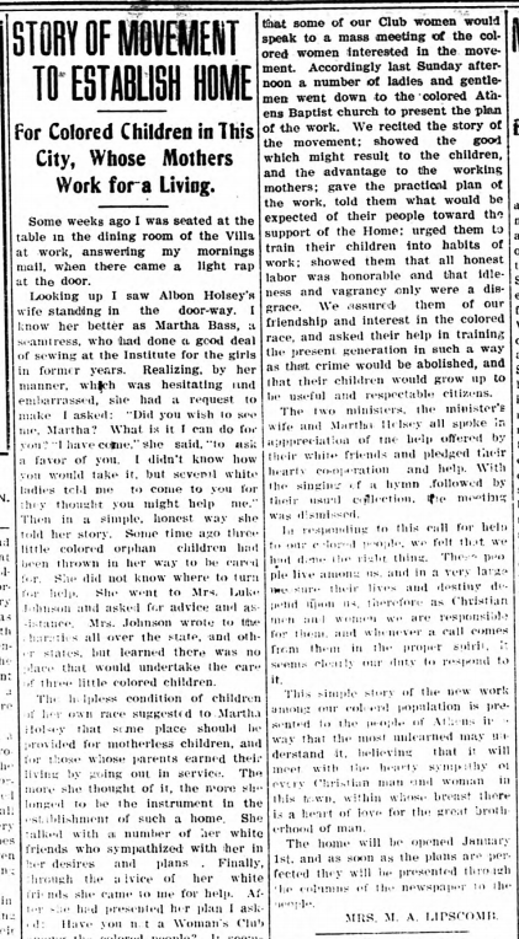

Title: Chase Street Elementary School Parent Teacher Association 1941-1942 scrapbook, page 36

URL: https://dlg.usg.edu/record/arl_ptos_sb-1941-42

Collection: Chase Street Parent Teacher Organization (PTO) scrapbooks

Courtesy of the Athens-Clarke County Library

Description: Caption: “Afghans for British relief made by Miss Mckie’s sixth grade – February 1941”

Title: Chase Street Elementary School Parent Teacher Association 1963-1966 scrapbook, page 4

URL: https://dlg.usg.edu/record/arl_ptos_sb-1963-66

Collection: Chase Street Parent Teacher Organization (PTO) scrapbooks

Courtesy of the Athens-Clarke County Library

Description: Seven boys are gathered for a candid group photo in front of Chase Street Elementary School, one is wearing a safety patrol sash belt, one is seated in a wheelchair, and another is using crutches.

Title: Chase Street Elementary School Parent Teacher Association 1963-1966 scrapbook, page 60

URL: https://dlg.usg.edu/record/arl_ptos_sb-1963-66

Collection: Chase Street Parent Teacher Organization (PTO) scrapbooks

Courtesy of the Athens-Clarke County Library

Description: Caption: “Safty[sic]” Patrol 1965-1966” (shows one of the first African American girls at Chase Street School in the desegregation era).

Title: Elementary School Parent Teacher Association 1966-1967 scrapbook, page 3

URL: https://dlg.usg.edu/record/arl_ptos_sb-1966-67

Collection: Chase Street Parent Teacher Organization (PTO) scrapbooks

Courtesy of the Athens-Clarke County Library

Description:

Caption: “Chase Street School Faculty 1966-1967. Principal: Mr. Robert C. Garrard” (Johnnie Lay Burks, the pioneering first African American teacher at Chase Street Elementary, is seated in the front row, first on the right)

![“Safty[sic]” Patrol 1965-1966” (shows one of the first African American girls at Chase Street School in the desegregation era). Chase Street Elementary School Parent Teacher Association 1963-1966 scrapbook, page 60.](https://mcusercontent.com/344ecc2c1b225f98f8389ce71/images/d13dbe72-a239-5990-e29c-fe71581e9c3f.jpeg)

![Sanborn Map Company. Insurance maps of Athens, Clark[e] County, Georgia](https://blog.dlg.galileo.usg.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Athens-Sanborn-Map-1.png)

![Sanborn Map Company. Insurance maps of Athens, Clark[e] County, Georgia](https://blog.dlg.galileo.usg.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Athens-Sanborn-Map-2.png)