This post is part of a series of guest contributions from our partners at HomePLACE, a project of the Georgia Public Library Service. HomePLACE works with Georgia’s public libraries and related institutions to digitize historical content for inclusion in the Digital Library of Georgia.

During the summer of 2018, Clayton State Masters of Archival Studies student Virginia Angles served as the inaugural HomePLACE Digitization Intern. Working on-site at the Mary Vinson Memorial Library, part of the Twin Lakes Library System in Milledgeville, Georgia, Virginia ushered a single item through the entire digitization process, from imaging and description through research and promotion. That item, a record book detailing the participants in a nursing training program operating at the Central State Hospital from 1910-1947, is now available in the Digital Library of Georgia. Below are her reflections after spending months working with and researching the record book.

As a Georgia HomePLACE intern I had the amazing opportunity to get to know the people of Milledgeville Georgia, explore the story of Central State Hospital (CSH), bring a new and unique piece of Central State Hospital Nursing History to light, and all the while gain hands-on experience seeing a digitization project from start to finish.

Over the summer I digitized a Milledgeville State Hospital Alumna Association Record Book newly found in the Twin Lakes Library System’s collections. This journal is handwritten and compiled by CSH nurse Rubye Cheeves and is a record of all the nursing students that graduated from the Hospital Nursing School. Amidst the huge amounts of information about the hospital’s history, very little is actually known about the nurses that served there. This book brings new context to what is already known about CSH and breathes new life into Milledgeville history.

During my research I had the opportunity to talk to many amazing people with deep family ties to Milledgeville and Central State Hospital. Many of these family roots began with the first generation of nurses moving to Milledgeville to serve the hospital. I was given many tours of the grounds, each time seeing something new and learning interesting facts. I was amazed to see many of the facilities still in use or in the process of revitalization. I was excited to see homes where the hospital staff stayed as I thought back over all of the names, addresses, and anecdotal information I had read in the record book.

The nurses and doctors lived on the hospital grounds as part of the compensation package. At the time CSH could not pay the hospital staff a competitive wage so they opted to provide housing instead. One of my tour guides even mentioned that the CSH cafeteria, currently being revitalized, was once the largest operating cafeterias in the world. It was an amazing feeling, connecting research with people and places.

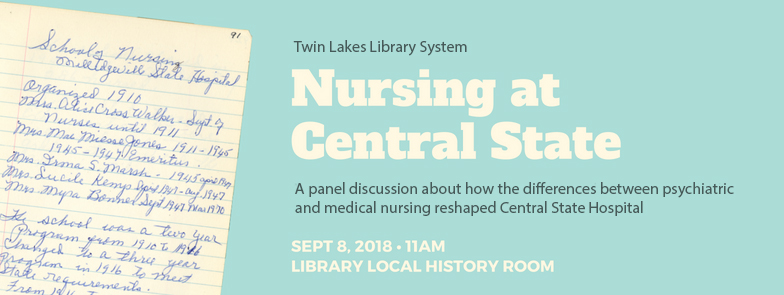

As my summer project has come to a close, I have one final thing to do. My final step is to create a public event and invite everyone to come, learn, and ask questions. I decided to gather a small group of retired CSH nurses and current Georgia College and State University Nursing Professors to sit down and discuss psychiatric and medical nursing and how changing nursing practices impacted the hospital and the community. One of the panelists, Georgia College Assistant Professor of Nursing Gail Godwin, has done extensive oral history research on participants in the nursing program, publishing her findings in her February 2018 Psychiatric Nursing article, “Lessons from the Light and Dark Sides of Psychiatric Clinical Experiences.”

Above all, I hope this panel discussion helps connect the community with their history, increases understanding of psychiatric nursing, and encourages more people to ask questions about their past.

View the Record book on Central State Hospital nursing students here.