In 2018, I curated an exhibit for the University of Georgia’s Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Titled “The New South and the New Slavery: Convict Labor in Georgia,” it examined the history of forced prison labor in Georgia beginning with the inception of the convict lease system in 1868 until its abolition in 1908, its transformation into the chain gang system that lasted until the 1940s, and its continuation with mass incarceration. After speaking with the Digital Library of Georgia and the New Georgia Encyclopedia about this project, they were enthusiastic about adapting the physical exhibit into a digital one. The online exhibition, The New South and the New Slavery, is the result of this collaboration.

As a scholar who specializes in late 19th- and early 20th-century African American and American Indian literature published in the periodical press, newspapers are among the first resources I consult when exploring a particular cultural or historical moment. I heeded the same process to investigate Georgia’s convict lease and chain gang systems. Coverage from the Atlanta Georgian and News and the Athens Weekly Banner was especially insightful. Some notable stories gleaned from these publications included: a mutiny on behalf of Black and white female prisoners in Milledgeville, the flogging of a female prisoner named Mamie de Cris, coverage of a hungry Georgia resident jailed for stealing a chicken, the testimony of an assaulted female prisoner, and reports of Athens-Clarke County’s demand for incarcerated populations for road construction surrounding the University of Georgia. More than ten newspaper accounts from the original Hargrett exhibit were found in periodicals digitized by the Georgia Historic Newspapers database.

What remains little-known of Georgia’s carceral systems is the fate of orphaned children whose parents were sentenced to labor in prison camps as well as the fate of those born in these camps. After insightful conversations with colleagues and visitors who toured the Hargrett exhibit, I began researching Black-run and -owned charitable institutions in Georgia. As anyone who has spent time steeped in the archives understands, one of the excitements of this kind of research is that, in searching for one story, you are often led to another. One such welcome surprise was the story of Martha Bass Holsey (ca. 1869-unknown), an African American upholsterer from Athens, Georgia, who reached across racial barriers in the Jim Crow South to establish a charitable home that served as an orphanage as well as a daycare for working Black families.

Reconstructing the story of Bass Holsey’s life and work has been aided by genealogical sites such as Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org, as well as US Census Records. Additionally, four major collections of the DLG have been instrumental—vital, actually—in this effort: Georgia Historic Newspapers, For Our Mutual Benefit: The Athens Woman’s Club and Social Reform, 1899-1920, Athens, Georgia city directories, and Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps for Georgia Towns and Cities, 1884-1941.

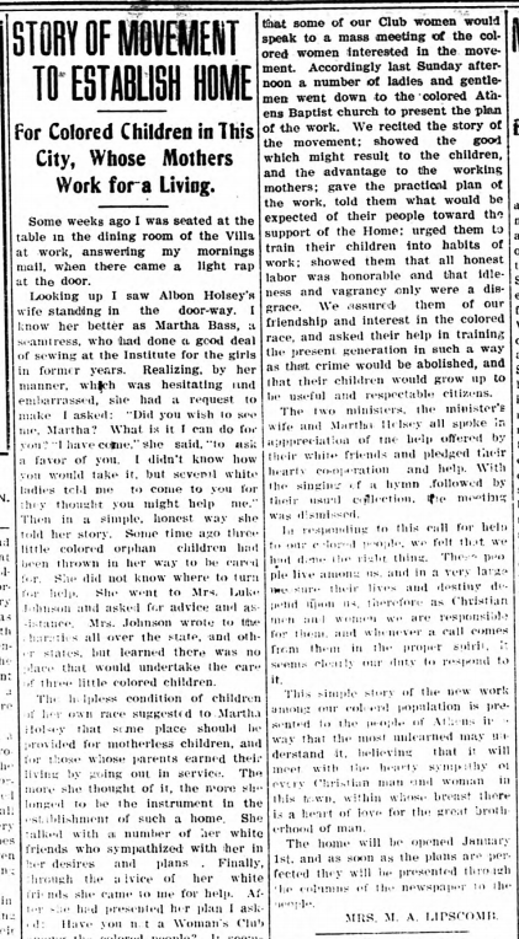

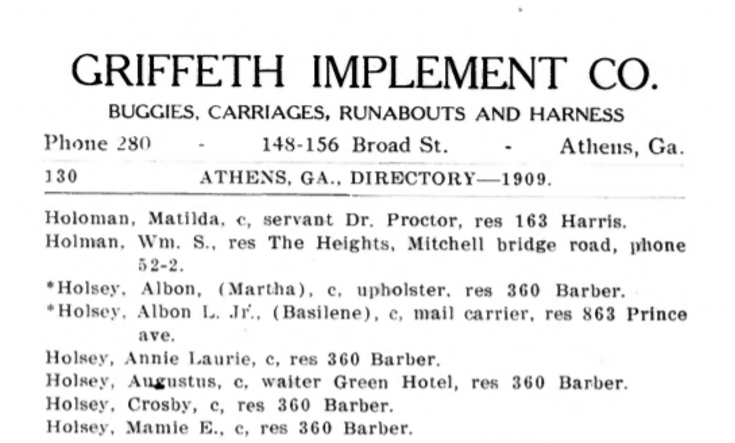

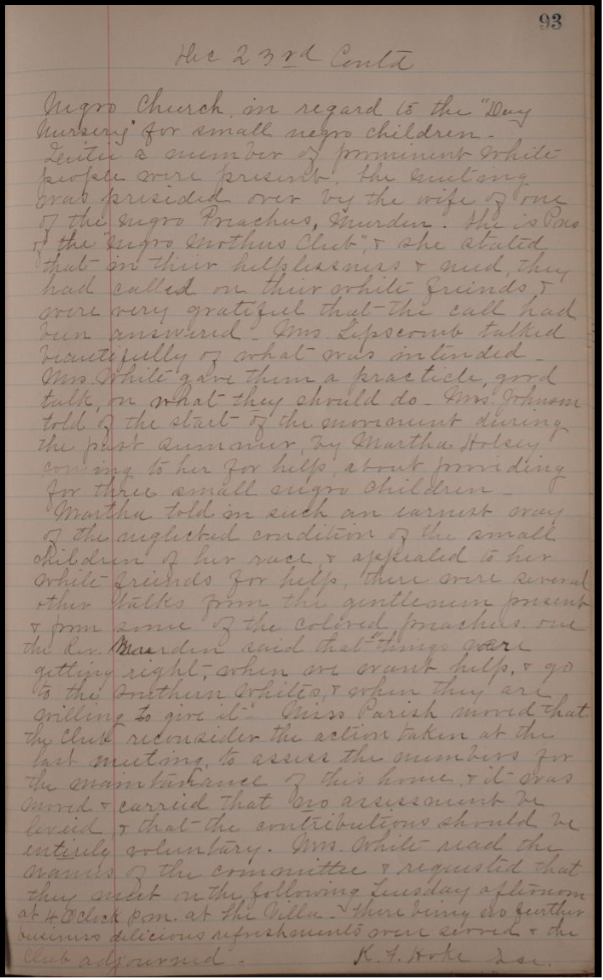

Martha Bass Holsey was born in Georgia in 1869, just after the Civil War. She lived for a long period of time in Athens, Georgia, where she worked variously as a dressmaker, upholsterer, seamstress, housekeeper, and nurse. In Athens-Clarke County in 1906, she married Albon Holsey, where they lived on Barber Street with their four children, Augustus, Crosby, Willie, and Mary. Newspaper accounts and meeting minutes of the Athens woman’s club detail Bass Holsey’s tireless, resourceful efforts to collaborate across racial lines to build an institution for Black Athenians. The story of her activism began to unfold with a 1907 report by Mary Ann Rutherford Limpscomb in the Athens Weekly Banner, in which Lipscomb recounted Bass Holsey’s plan for the orphanage and daycare. Because the local African American women’s club lacked the necessary funds to build an orphanage, Bass Holsey in 1907 approached Lipscomb, who was then the president of the Georgia Federation of Women’s Clubs and a member of the local white Athens woman’s club. Together, they charted a plan: Bass Holsey would locate a suitable house to rent and a matron to care for the children, and Lipscomb would enlist the woman’s club to provide funds. In December that year, Bass Holsey, members of the Black community, and Lipscomb and her fellow woman’s club members gathered at the local African American Baptist Church to deliberate. The Home opened in January 1908. It was supported by both white and Black Athenians. The Home’s ongoing success was due in large part to Black residents of Athens, who regularly donated food and money.

There is much that remains unknown about Bass Holsey’s life beyond her institution-building initiatives. The death of Albon in 1913 left her widowed. While her whereabouts after his death are yet unclear, there are ample records of her two sons, Augustus (ca. 1889-1967) and Crosby (ca. 1893-1962), who served in the US military in World War I. Augustus attended Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia, before leaving school to enlist in the war, during which he served with a field artillery unit. He retired as a post office carrier in Baltimore, Maryland, and he is buried in Baltimore National Cemetery. Crosby enlisted in World War I, as well, and he served as a cook in the 365th Infantry. After the war, he worked as a railroad porter in Baltimore, where he lived with Augustus and Augustus’s wife, Estella. There are more gaps to fill with regard to the Holsey family history.

Until recently, a looming question remained: Where was the Home located? I spoke to David Mitchell, the Executive Director of the Atlanta Preservation Center, who suggested consulting Sanborn Fire Maps. Thanks to the DLG’s extensive digitized archive of Sanborn maps, the former site of the orphanage and daycare has been located in the Reese Street Historic District. The Home once stood near what is now the Athens Masonic Association, formerly Athens High and Industrial School, the first Black public high school in Georgia. Just a few blocks away from the Home would have been the Knox Institute, a Black school opened by the Freedmen’s Bureau just after the Civil War. While Bass Holsey’s Home, like the Knox Institute, no longer stands, its history is another salutary reminder of this neighborhood’s position as a rich site of early Black institution-building.

Bass Holsey’s and the Home’s story continues. Conversations, chance discoveries, and the addition of newly digitized newspapers and other records will, I hope, turn up new information. The next step? To find some way to visibly, publicly acknowledge this culturally significant site that adds yet another layer to the story of Black history and early Black activism in Athens.

Illustrations

“Story of Movement to Establish Home.” The Athens Banner, Dec. 13, 1907, p. 10. Courtesy of Georgia Historic Newspapers, https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/lccn/sn88054098/1907-12-14/ed-1/seq-10/.

Directory, City of Athens, Georgia [1909]. Athens Directory Company: 1909, p. 128. Courtesy of University of Georgia, Map and Government Information Library, https://dlg.usg.edu/record/dlg_acd_acd1909.

Minutes 1899-1911, p. 93. Athens Woman’s Club collection, Heritage Room, Athens-Clarke County Library, Athens, Ga., as presented in the Digital Library of Georgia. https://dlg.usg.edu/record/dlg_awcm_awc001

![Sanborn Map Company. Insurance maps of Athens, Clark[e] County, Georgia](https://blog.dlg.galileo.usg.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Athens-Sanborn-Map-1.png)

![Sanborn Map Company. Insurance maps of Athens, Clark[e] County, Georgia](https://blog.dlg.galileo.usg.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Athens-Sanborn-Map-2.png)

Sanborn Map Company. Insurance maps of Athens, Clark[e] County, Georgia, April 1908, p. 8. University of Georgia Libraries Map Collection, Athens, Ga., presented in the Digital Library of Georgia. https://dlg.usg.edu/record/dlg_sanb_athens-1908#item

—Sidonia Serafini, Ph.D. candidate in English, University of Georgia