In partnership with Special Collections & Archives at the University of North Georgia, the Digital Library of Georgia (DLG) has digitized school yearbooks dating from 1975 to 1995. This period covers the years leading up to the second name change for North Georgia College (which became North Georgia College & State University) and its growth from a college to a university.

This project contained approximately 4,700 pages in 20 bound volumes that document how (then-) North Georgia College (NGC) saw extensive growth during this time, thus demonstrating its high research value as a digitized collection.

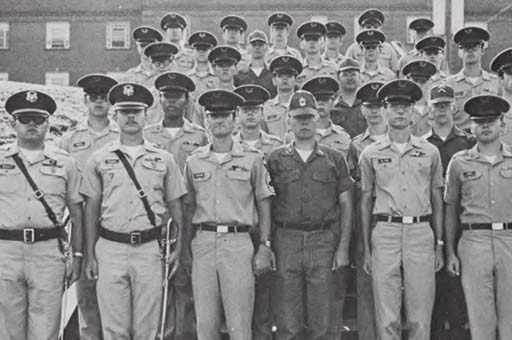

Dr. John H. Owen (1922-2011), a lieutenant commander in the United States Navy, was named the twelfth president of North Georgia College (NGC) in 1970. During his tenure, the enrollment of North Georgia College (now the University of North Georgia) nearly tripled, thanks to having produced more course offerings and programs, having integrated the campus in 1967, and having enrolled women military cadets beginning in 1973.

NGC saw significant changes in the late 1960s and early 1970s. For example, in 1967, NGC integrated, and in 1973 women were included in the Corps of Cadets. The effects of these policy changes shaped campus culture from 1975 to 1995.

Dr. Owen stepped down as president in 1992, and the vice president for academic affairs, anatomist Delmas J. Allen was named president. Dr. Allen served as president from 1993 to 1996 and managed the school’s transition from a college to a university due to the changes in student body population and faculty/staff demographics that followed nearly two decades of growth for the school and the region.

The makeup of the student body, the increase in student organizations, the addition of inclusive multicultural groups, and the expansion of the faculty/staff of the college all reflect the more significant demographic shifts in Northeast Georgia, and thus the university. In addition, most students at NGC during this time were from Northeast Georgia. Because of this, the Cyclops collection also serves as an essential historical representation of the Northeast Georgia region.

Wendi D. Huguley, the University of North Georgia’s Director of Alumni Relations and Annual Giving, emphasizes the value that these digitized volumes have: “Our office frequently sends digital yearbook links to family members, alumni, reunion groups and University staff who contact us requesting materials picturing their loved ones, classmates, or former colleagues. The online access to these records provides ease of use for anyone who is searching for their memories.”

Special Collections & Digital Initiatives Librarian Allison Galloup welcomes questions about the digitization project and can be reached at Allison.Galloup@ung.edu

[View the entire collection online]

About the University of North Georgia. Special Collections & Archives, Dahlonega Campus (Dahlonega, Ga.)

The Special Collections and Archives serve as the institutional memory of the university and its predecessors, Gainesville State College, and North Georgia College and State University. In addition, the Special Collections and Archives seeks to collect, arrange, preserve and make accessible collections related to the history of Appalachia, Northeast Georgia, and the communities surrounding the university’s five campuses. You can find out more at ung.edu/libraries/sc-archives/index.php.

Selected images from the collection:

Title: Cyclops 1975, vol. 68, page 58

Description: Band Company, 1975.

URL: https://dlg.usg.edu/record/gnd_yearbooks_61

Image courtesy of University of North Georgia Special Collections & Archives

Title: Cyclops, 1995, vol. 88, page 183

Description: Cheerleaders, 1995.