From January 19 to April 16, 2021, I held the position of online exhibit intern for the Digital Library of Georgia and the New Georgia Encyclopedia. The internship brief was to design an exhibit on my chosen topic, selecting all multimedia objects and organizing them into discrete thematic sections before writing exhibit copy.

I had initially approached this project thinking that I should create an exhibit about something closely tied to my degree and dissertation research, which was, to be fair, not about Georgia at all: I had spent my doctoral career studying Renaissance English literature and medical history.

I mulled over potential exhibit topics on Georgia medical history, like the founding of hospitals and medical schools, before I reconsidered the purpose of curating an exhibit.

I decided that the point was not to curate exhibit content for its own sake simply because it’s available information, just as you don’t teach a class about certain texts just because you’ve read them. The content should tell a story that the audience might not know yet, but that, once known, will change something about their perspective and understanding of the world. So instead of asking myself what I already knew, I asked the opposite: what did I not know? What stories had I not heard yet?

I grew up in a small mountain town near the border of Georgia and North Carolina, and I thought about the absolute invisibility of LGBTQ+ experiences in that community. Even in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, subjects like LGBTQ+ rights and pride could be dangerous to raise, and as a result, they often simply weren’t. Every single LGBTQ+ person I knew in my hometown, myself included, waited to “come out” until they had moved to a city like Raleigh or Atlanta, where it felt safe to be visible. We were all recovering the history of our community late, and it seemed like there was so much we didn’t know. So, I scrapped one proposal and wrote another for an exhibit on LGBTQ+ history in Georgia to tell the stories I hadn’t heard yet.

I found during the proposal process that there were important efforts I had already begun to collect, preserve, and retell:

- The work of the “Atlanta Lesbian and Gay History Thing” established in 1988;

- Wesley Chenault’s exhibit “Atlanta Since Stonewall, 1969-2009: A Local History;

- The book Chenault co-authored with Stacy Braukman, Gay and Lesbian Atlanta;

- Georgia State University’s exhibit “Out in the Archives” draws on its Gender and Sexuality Collections.

- There are research centers like the LGBTQ Institute at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights; preservation initiatives like Historic Atlanta’s LGBTQ Historic Preservation Advisory Committee and the cross-institutional Georgia LGBTQ Archives Project; and repositories like the Invisible Histories Project focused on the Southeast.

I couldn’t create an exhibit that would cover all grounds in Georgia LGBTQ+ history, so I narrowed my focus to a sub-topic that inspired me: art history.

I am grateful in this process to have had both clear directions from DLG/NGE staff as well as the freedom to conduct the work in ways that made sense to me. I began by sifting through the collections of digitized materials aggregated by the DLG, and because I had to read and examine individual items in order to determine their potential relevance to my project, I learned an enormous amount about LGBTQ+ history in Georgia more broadly.

As I learned, I also found myself responding emotionally to remnants of pain, joy, anger, and love in the archives. When I read about Tom Fox’s death from AIDS, chronicled in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, my heart ached; when I read the tender poetry of 1970s Radical Faeries, it soared. Every day of initial research involved entering an odd state of mind combining clinical observation with empathy pulling in unpredictable directions as I encountered new objects and stories. Nothing I had ever researched before had been so powerfully moving, and I ended each shift feeling exhausted and inspired. Even when I came across materials that for one reason or another wouldn’t be a good fit for the exhibit, I often felt compelled to share them, and I found myself linking friends to interesting materials represented in the DLG and starting conversations about them.

The themes and sub-themes for the exhibit emerged organically as I collected materials about creators, creations, and communities. Once I had arranged them, I began the process of doing secondary research to flesh out the context surrounding them. In this process, too, I learned more than I could possibly fit into the exhibit. I became familiar with timelines of LGBTQ+ activism in Georgia; with the histories of LGBTQ+-serving businesses and collectives, many of which had already come and gone; and with figures I had known little about, but whose artistic influences spread widely in Georgia. I excitedly told friends and family what I had learned each week, in that way spreading information before the exhibit was accessible to the public.

The exhibit itself (while not yet finalized) is something I’m truly proud of because creating it required skills that I already possessed and enjoyed using–like researching nitty-gritty details–as well as skills that were newer. I had to find a balance in copy drafting, for example, between describing moments of historical trauma with the gravity they deserve and not allowing narratives of struggle to dominate the exhibit and drown out other LGBTQ+ experiences and emotions expressed in art.

I also had to think as much as possible about the audiences that might see the exhibit and what would be meaningful, memorable, and clear to them. I have a tendency picked up from years of old-fashioned academic writing of composing long, winding sentences (you can even see them in this report), and it’s useful for me to have to edit and revise for clarity.

I’m proud of the amount of content I was able to locate, organize, and contextualize in what seemed like a short amount of time without losing focus or a sense of the ‘bigger picture’ and purpose that the exhibit was to serve. I’m proud, too, that the result of this project will be a public-facing artifact. In my graduate career I have not had many opportunities to communicate research outside of classrooms and conferences, and this fact sometimes left me feeling disconnected, like my work lacked “real world” applications or relevance. With this exhibit, I felt the relevance acutely.

Moving forward in my career, as I transition out of professional academia toward other pathways, I will be able to show potential hiring committees concrete evidence of my ability to manage projects from start to finish, prepare digital content, work with members of a larger team, and more. I will be able to showcase fact-based and creative content, educational and (I hope) entertaining. I can demonstrate that I am not limited to only writing obscure academic papers aimed at specialist audiences but can create more accessible content. I do intend to apply for museum positions, where the ability to communicate to the public and arrange objects into stories will be especially useful, but I am also considering consulting positions that would apply the same skills to more abstract content.

Finally, beyond fostering professional skill development, working on this project has made me feel more connected with my identity as a queer woman. Even as a ” straight-passing adult,” I have sometimes wondered how visible I should or shouldn’t be or whether it’s safe to express myself authentically. Queer Georgians before and around me, as seen in this exhibit, have already paid high prices and made long strides for the privilege. I now have to be open about my identity; I cannot afford to ignore a gift that precious. Putting together the exhibit has also allowed me to feel connected to a larger community that I haven’t been among in what feels like a long time due to the pandemic. It’s been easy to feel isolated; it’s more difficult to feel that way when in the mental company of queer Georgian individuals and collectives across other times and places.

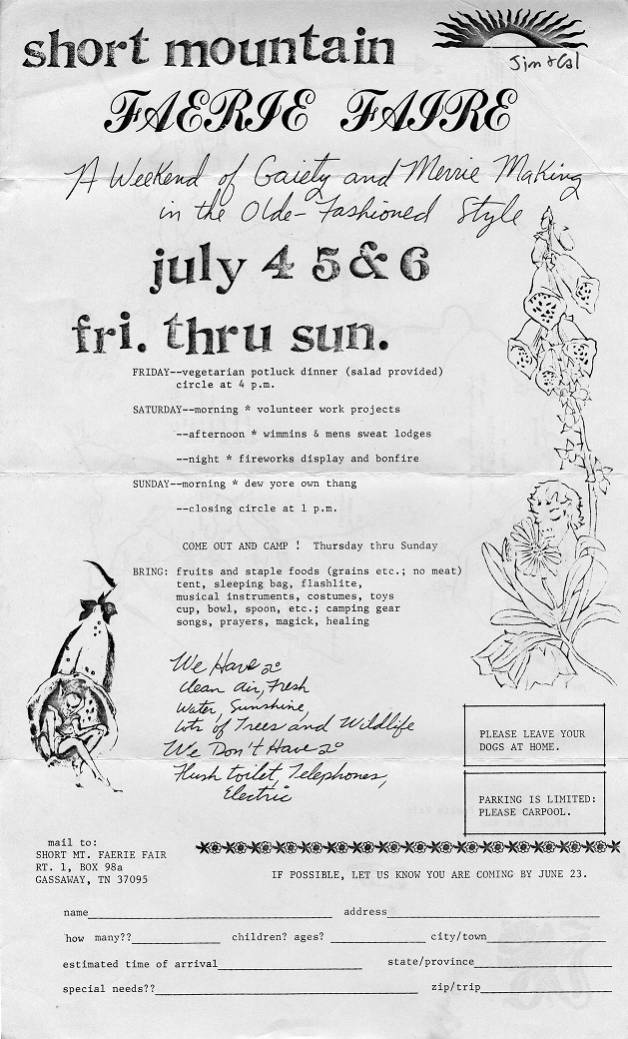

Image credit: Form letter invitation to the Short Mountain Faerie Faire, Short Mountain, Tennessee, July 4 – 6, 1980. (1 leaf, recto and verso, on pink paper).

Courtesy of Georgia State University Library Digital Collections

https://dlg.usg.edu/record/gsu_lgbtq_146

–Sarah Mayo