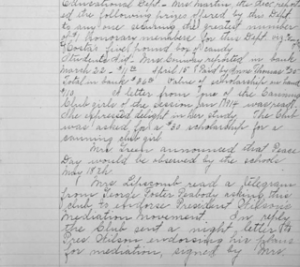

Home canning has regained popularity with Americans sharing a renewed interest in locally-grown food, handmade goods, and household thrift. Canning equipment sales are booming despite lean economic times, canning parties and can swaps are sprouting up throughout the country, and delicious recipes designed for storage in glass jars have recently shown up in cookbooks and food blogs everywhere. Many of these new home canners are enthusiastic hobbyists, working in small batches, and sharing amongst friends. Until recently, however, most canners did so out of necessity. Georgia boasts a history of industrious people who not only generated vast quantities of preserved goods, but whose canning efforts fortified the land that they farmed from, secured educational opportunities that had not previously existed, and supported national defense efforts. Resources about these people and their activities can all be found in the Digital Library of Georgia.

Georgians had embraced home canning as a common household practice by the mid-to-late nineteenth century. Most kitchens, both on the farm and in town, likely contained some version of an airtight screw cap and glass jar: either one that was patented by John Mason in 1858, or any number of similar jars that were patented shortly afterward. An advertisement for “Mason’s Patent Screw-Top Fruit Jar” is available in the June 26, 1869 issue of the Macon Daily Telegraph.

After the harvest bounty was preserved, these home-canned goods were judged in contests at state and local fairs. Winners of these competitions received prizes or “premiums,” and their names were printed on the front pages of local newspapers. The November 16, 1877 edition of the Weekly Sumter Republican describes a variety of preserved foods that received awards from the Americus Fair Association. Among the many items entered in the competition were: Mrs. Dr. E. J. Eldridge’s jars of pickled onions and walnut catsup, Mrs. E. B. Rosa’s mangoes, Miss Mollie Hawkins’ brandy peaches, Mrs. C. M. Wheatley’s “May haw” jelly, and Mrs. S. M. McGarrah’s jars of preserved watermelon and peaches preserved without sugar.

By the early twentieth century, rural girls joined “canning clubs,” agricultural organizations that preceded cooperative extension programs and 4-H clubs; here, girls learned how to cultivate and preserve tomatoes. Some of these “canning club girls” can be seen in a 1916 photograph from Rabun County. Also known as “tomato clubs” throughout the South, these organizations were established for young women as the counterpart to boys’ “corn clubs;” all were part of a Southern initiative overseen by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to encourage crop diversity and mitigate the impact of the boll weevil. Both corn and tomatoes grew plentifully in Southern soil, and both crops generated profits. Tomatoes, which required minimal processing for longer-term storage, could be preserved quickly and efficiently in the Southern home kitchen; conveniently, their natural acidity hindered spoilage.

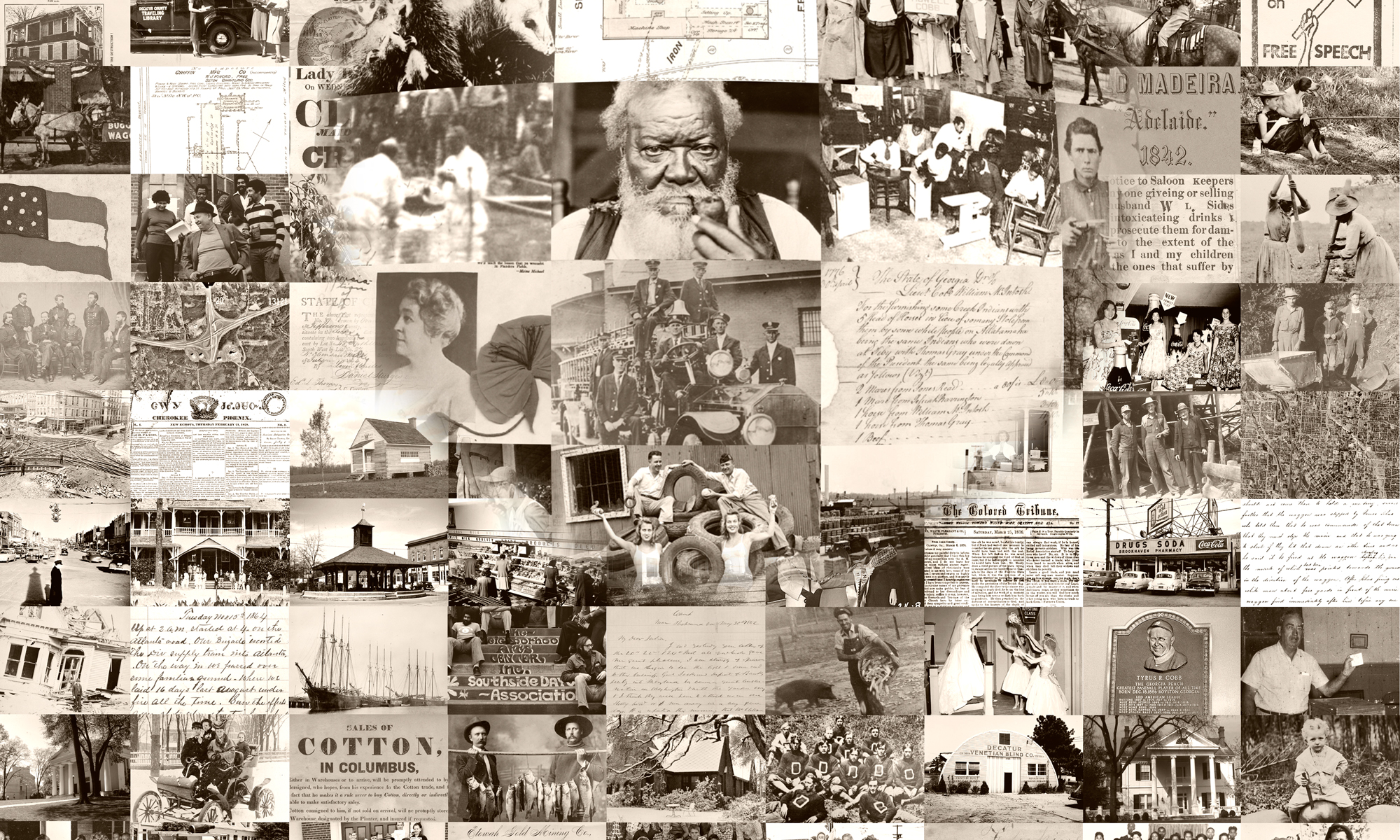

In Georgia, canning clubs became extremely popular; thousands of girls were instructed and supervised by home demonstration or “canning” agents across the state’s participating counties. In addition to demonstrating safe canning processes and efficient kitchen management, home demonstration agents also provided young women with food cultivation and financial management skills. The girls planted small plots that yielded tomatoes for the household, as well as fresh and canned tomatoes that would be sold. They were shown how to sterilize and seal both glass jars and tin cans; in the case of the latter, girls were also trained how to solder the cans shut. Additionally, the girls were required to keep detailed and accurate crop records, as well as descriptive accounts of their work. When this was complete, they presented their wares in canning displays that were set up at agricultural shows and state fairs, much like this 1920 exhibit from a Bibb County girls’ canning club. They also sold their tomatoes under their own names. A December 15, 1911 article in the Athens Weekly Banner refers to the crop records kept by a successful canning club girl. Miss Louise Hardeman, a member of the Clarke County canning club and the recent winner of the state’s canning contest, made $25.00 in net proceeds from a harvest of 2, 155 pounds of tomatoes that she grew on one-tenth of an acre–this would be about $577.57 today.

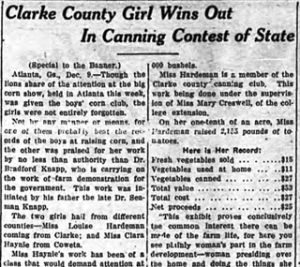

Canning club girls also displayed their work in local fraternal organizations: early on, they found sponsorship from women’s clubs and town benefactors who not only purchased canning club products, but also made charitable contributions in the form of scholarships and awards. A 1914 entry in an Athens Woman’s Club minute book on page 55 notes that “A letter from one of the Canning Club girls of the session Jan 14 was read. She expressed delight in her study. The Club was asked for a $30.00 scholarship for a canning club girl.” Another entry from 1916, on page 110, encourages the purchase of canning club goods: “Mrs. Shelton moved a committee be appointed to see the merchants and ask if we have at least twenty women to buy these Canning Club products, if they will carry them. The motion carried and Mrs. Green asked Miss Hill to appoint this committee. ”

Congress’ passage of the Smith-Lever Act on May 8, 1914 (co-sponsored by Georgia senator Hoke Smith) formally established cooperative extension services at land-grant universities. Most land-grant institutions in Southern states signed cooperative agreements with the USDA and created cooperative extension departments. The University of Georgia created the UGA Cooperative Extension Service, and absorbed the canning clubs as part of its 4-H youth program (because the University of Georgia and 4-H programs were segregated, African American cooperative extension activities were headquartered at Savannah State College until 1967; an African American 4-H center was established in Dublin, Ga. in 1939). This increased cooperation between canning clubs and the state land-grant institution was uniquely beneficial for white Georgia women eager to enroll in higher education. The clubs demonstrated a visible economic value for domestic activities, and of course, a growing demand for home demonstration workers who required instruction and training. Because of this, Georgia’s progressive women’s club members were able to shrewdly leverage the popularity and financial success of the canning clubs for greater access to women seeking higher education. In 1918, the Georgia State College of Agriculture of the University of Georgia approved the first degree program for women, and the university awarded its first undergraduate degree to Mary Ethel Creswell in 1919. An entry from the Red and Black from October 29, 1913 notes Creswell’s resignation as the head of the Girls’ Canning Club for a “government service position” (she served as a field agent for the USDA, where she became their first female supervisor, and later became the first dean of UGA’s School of Home Economics). Other new college girls followed her path; many of whose tuition payments and scholarships were secured by proceeds from the sale of canned tomatoes.

National agricultural clubs like 4-H and Future Farmers of America continued to seek ways to improve food production and promote food preservation, which they did by setting up exhibits at state fairs. Several photographs from the Georgia State Fair include a 1927 exhibit of canned goods from Bibb County 4-H members and a community canning demonstration that promoted the civilian war effort during World War II, when “victory gardens” or “war gardens” were grown on home and community plots so as to minimize demand for the commercial crops that fed American soldiers. Local clubs encouraged food preservation as well, as shown in this 1953 photograph of a member of Cobb County’s Lost Mountain Community Improvement Club canning vegetables, and a “Home Demonstration Club” display at the Winder Fair in Barrow County.

If you are eager to try canning yourself, current resources on home food preservation are available at the National Center for Home Food Preservation, hosted by the University of Georgia’s College of Family and Consumer Sciences. Here you can also find research-based recommendations on food preservation provided by the USDA, the University of Georgia Cooperative Extension Service, and other land-grant universities in the Cooperative Extension System.