Selected by statewide cultural heritage stakeholders and funded by the DLG’s competitive digitization grant program, this collection is the Walter J. Brown Media Archives’s fourth collaboration with the DLG and is available here: https://dlg.usg.edu/collection/ugabma_wwlaw.

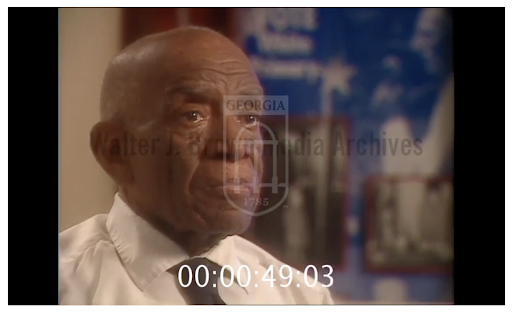

The content for this project consists of oral history interview videos with W. W. Law and other Savannah, Georgia, community members involved in the Civil Rights movement. The tapes were shot just prior to Mr. Law’s death and are the longest and most detailed interviews he did on his life and career as a Civil Rights activist.

The footage was shot in 2001 by Lisa Friedman with the help of the late oral historian Cliff Kuhn for the purpose of creating a documentary on the life of W. W. Law. Although that project never came to completion, it still managed to yield important historical content about Savannah civil rights workers and community leaders, including Aaron Buschbaum, Dr. Clyde W. Hall, Edna Branch Jackson, Ida Mae Bryant, Rev. Edward Lambrellis, Richard Shinholster, Tessie Rosanna Law, Dr. Amos C. Brown, Mercedes Arnold Wright, Carolyn Coleman, E.J. Josey, Walter J. Leonard, and Judge H. Sol Clark.

W. W. Law was fired from his job working for the post office in 1961 because of his civil rights work but was reinstated after an intervention by NAACP leaders and U.S. President John F. Kennedy. As with all civil rights movements in American towns and cities, stories of lesser-known activists in the Civil Rights Movement and the historical impact made by community leaders like Law and the others interviewed in this project are invaluable for researchers interested in the history of civil rights in Georgia.

Luciana Spracher, director of the City of Savannah Municipal Archives, defines the importance of digital access to this content and the stewardship of this audiovisual work that was granted to the Brown Media Archives and made accessible through this DLG subgrant:

“The City of Savannah Municipal Archives’s W. W. Law Collection represents his life’s work, as left behind by him at the time of his death in 2002. The Walter J. Brown and Peabody Awards Collection’s collection of W. W. Law material includes video interviews where Mr. Law discussed his life and legacy less than a year before his death, as well as interviews with people, well-represented in the papers of our collections that document civil rights activities in Savannah. Both collections complement and enhance understanding of the other. The opportunity to hear these individuals recall the events represented in our collections is invaluable to students and historians who are studying and learning from them. Greater discoverability of the interviews online will assist researchers in seeking insight into the Civil Rights Movement in Savannah, as well as the larger Movement in Georgia and the United States.”

[View the entire collection online]

###

About the Walter J. Brown Media Archives and Peabody Awards Collection:

The Walter J. Brown Media Archives & Peabody Awards Collection is home to more than 350,000 analog audiovisual items, over 5,000,000 feet of newsfilm, and over 200,000 digital files. It is the third-largest broadcasting archive in the country, behind only the Library of Congress and the UCLA Film & Television Archive. The Archives comprise moving image and sound collections that focus on American television and radio broadcasting and Georgia’s music, folklore, and history; this includes local television news and programs, audio folk music field tapes, and home movies from rural Georgia. In the Peabody Collection alone, there are more than 50,000 television programs and more than 39,500 radio programs. Its mission is to preserve, protect, and provide access to the moving image and sound materials that reflect the collective memory of broadcasting and the history of the state of Georgia and its people. Learn more at libs.uga.edu/media/index.html

About the Digital Library of Georgia

The Digital Library of Georgia (DLG) serves as Georgia’s statewide cultural heritage digitization initiative. It is a joint project between the University of Georgia Libraries and GALILEO. The DLG collaborates with Georgia’s cultural heritage and educational institutions to provide free online access to historic resources on Georgia. The DLG not only develops, maintains, and preserves digital collections and online resources, but also partners to build digitization capacity and technical infrastructure. It acts as Georgia’s service hub for the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) and facilitates cooperative digitization initiatives. The DLG serves as the home of the Georgia Newspaper Project, Georgia’s print journalism preservation project.

Visit our website at dlg.usg.edu

Facebook: http://facebook.com/DigitalLibraryofGeorgia/

Twitter: @DigLibGA

Instagram: @diglibga

Subscribe to our listserv